Posted on Jun 24, 2022

Injured American Veterans and the Disability Rights Movement

1.02K

30

5

14

14

0

Edited >1 y ago

Posted >1 y ago

Responses: 3

Thank you my friend MAJ Dale E. Wilson, Ph.D. for posting the perspective from roadstothegreatwar-ww1.blogspot.com author Ryan Reft

Images:

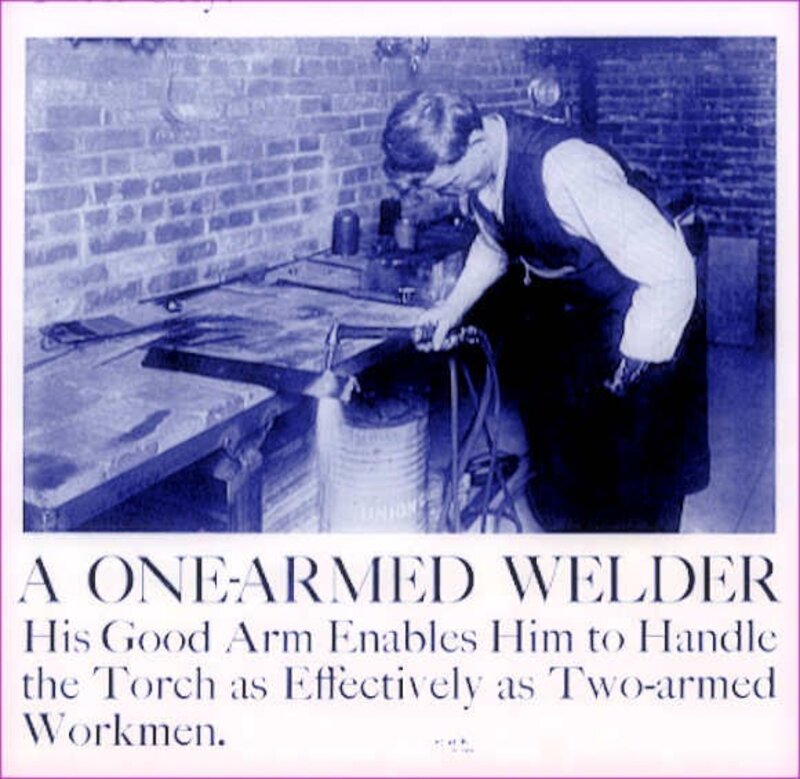

1. One-armed welder. His good arm enables him to handle the torch as effectively as two-armed workmen.

2. Facing the future; Unlce Sam offers training to every man disabled in the service. See that your man takes it. Ask the Red Cross

3. Future ship workers. Disabled man are taught to Oxy-acetaline weliding in the Red Cross Institute for cripled and disabled me, New York City.

Background from {[http://roadstothegreatwar-ww1.blogspot.com/2022/06/injured-american-veterans-and.html}]

Fans of the HBO series Boardwalk Empire may remember that World War I veterans grappling with disability occupied a critical place in the show’s story. Fictional vet Jimmy Darmandy (Michael Pitt) struggled as much with PTSD as he did with a limp derived from shrapnel embedded in his leg by a German grenade. Richard Harrow (Jack Huston), on the other hand, endured facial disfigurement so severe he wore a mask to conceal his injuries, though his wounds went far beyond the physical.

Artifacts on display in the Library of Congress exhibit Echoes of the Great War: American Experiences of World War I demonstrate the human cost of the war, the government’s response and the ways in which injured veterans helped push forward—even if in a somewhat limited fashion—the disability rights movement.

During the war 224,000 soldiers suffered injuries that sidelined them from the front. Roughly 4,400 returned home missing part or all of a limb. Of course, disability was not limited to missing limbs; as the Boardwalk Empire characters demonstrate, a soldier could come home with all limbs and digits intact yet struggle with mental wounds. Nearly 100,000 soldiers were removed from fighting for psychological injuries; 40,000 of them were discharged. By 1921, approximately 9,000 veterans had undergone treatment for psychological disability in veterans hospitals. As the decade progressed, greater numbers of veterans received treatment for “war neurosis.” Ultimately, whether mental or physical, 200,000 veterans would return home with a permanent disability.

“[A] man could not go through that conflict and come back and take his place as a normal human being,” veteran and former infantry officer Robert S. Marx noted in late 1919. Marx played a critical role in establishing the organization Disabled Veterans of the World War (DAV) in 1920. He knew well the sting of disability: just hours before the war’s ceasefire, he suffered a severe injury after being wounded by a German artillery shell.

With the larger American Legion, founded in 1919, the DAV worked to raise public awareness about disabled veterans, while pressuring the government to adopt programs to address their rehabilitation and reintegration into American society. Though far smaller than the American Legion, which claimed 850,000 members within its first year of its existence, DAV membership rolls topped 25,000 by 1922 and had 1,200 local chapters and state offices nationwide. Overlap between the DAV and the Legion was unmistakable; roughly 90 percent of DAV members were also legionnaires. In fact, Marx helped to found the Legion’s National Rehabilitation Committee.

Together, the two organizations placed veterans’ disability at the forefront of the push for veterans’ rights and benefits, including for “shell shock” or what today would be classified as PTSD. Due to the organizations’ efforts, in 1921 the U.S. government established the United States Veterans Bureau, a precursor to today’s U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

The Red Cross and the government also acted independently to address disability. In 1917, the Red Cross opened the first institution dedicated to training amputees and individuals with damaged limbs—The Institute for Crippled and Disabled Men in New York City. Though not initially established for veterans, the institute soon found itself inundated with World War I soldiers. In addition to rehabilitating injured soldiers, the institute produced and distributed 50 pamphlets, broadsides and books focusing on rehabilitation in the first year after the Armistice. During 1918, the institute distributed six million copies of “Your Duty to the War Cripple” to New Yorkers.

The government established the Federal Board for Vocational Education in 1917; it produced the first studies on veterans’ disability. The following year, the Smith-Sears Vocational Rehabilitation Act passed, providing for rehabilitation and vocational training for disabled veterans.

Despite these efforts, the treatment of disabled veterans varied widely, and attempts to streamline it largely failed. Veterans lodged numerous complaints related to poor dining, housing and rehabilitation facilities. Counselors, meant to help steer veterans toward rehabilitation and vocational training, were seen by many veterans as distant and uncommunicative. Black veterans endured racial discrimination, greatly diminished facilities, and systematic neglect.

Of the roughly 330,000 veterans eligible for rehabilitation, nearly half received some amount of training. It came with a steep price tag, however; in 1927 alone, the cost of rehabilitation exceeded $400 million. The following year, the vocational education board expended half a billion dollars in compensation for veterans.

Though not exactly a success story, the government’s role in rehabilitation did expand the development and institutionalization of the veterans’ welfare and demonstrated a commitment to restoring veterans to societal productivity.'

FYI Lt Col Charlie Brown MAJ Byron Oyler Maj Robert Thornton SSgt David M. MAJ Roland McDonald MAJ Bob Miyagishima Maj Bill Smith, Ph.D. SFC William Farrell PO3 Edward Riddle Kim Bolen RN CCM ACM 1LT (Anonymous) SPC Michael Duricko, Ph.D SPC Michael Terrell SFC Joe S. Davis Jr., MSM, DSL SMSgt Tom Burns SMSgt David A Asbury SGT Jim Arnold PVT Mark Whitcomb

Images:

1. One-armed welder. His good arm enables him to handle the torch as effectively as two-armed workmen.

2. Facing the future; Unlce Sam offers training to every man disabled in the service. See that your man takes it. Ask the Red Cross

3. Future ship workers. Disabled man are taught to Oxy-acetaline weliding in the Red Cross Institute for cripled and disabled me, New York City.

Background from {[http://roadstothegreatwar-ww1.blogspot.com/2022/06/injured-american-veterans-and.html}]

Fans of the HBO series Boardwalk Empire may remember that World War I veterans grappling with disability occupied a critical place in the show’s story. Fictional vet Jimmy Darmandy (Michael Pitt) struggled as much with PTSD as he did with a limp derived from shrapnel embedded in his leg by a German grenade. Richard Harrow (Jack Huston), on the other hand, endured facial disfigurement so severe he wore a mask to conceal his injuries, though his wounds went far beyond the physical.

Artifacts on display in the Library of Congress exhibit Echoes of the Great War: American Experiences of World War I demonstrate the human cost of the war, the government’s response and the ways in which injured veterans helped push forward—even if in a somewhat limited fashion—the disability rights movement.

During the war 224,000 soldiers suffered injuries that sidelined them from the front. Roughly 4,400 returned home missing part or all of a limb. Of course, disability was not limited to missing limbs; as the Boardwalk Empire characters demonstrate, a soldier could come home with all limbs and digits intact yet struggle with mental wounds. Nearly 100,000 soldiers were removed from fighting for psychological injuries; 40,000 of them were discharged. By 1921, approximately 9,000 veterans had undergone treatment for psychological disability in veterans hospitals. As the decade progressed, greater numbers of veterans received treatment for “war neurosis.” Ultimately, whether mental or physical, 200,000 veterans would return home with a permanent disability.

“[A] man could not go through that conflict and come back and take his place as a normal human being,” veteran and former infantry officer Robert S. Marx noted in late 1919. Marx played a critical role in establishing the organization Disabled Veterans of the World War (DAV) in 1920. He knew well the sting of disability: just hours before the war’s ceasefire, he suffered a severe injury after being wounded by a German artillery shell.

With the larger American Legion, founded in 1919, the DAV worked to raise public awareness about disabled veterans, while pressuring the government to adopt programs to address their rehabilitation and reintegration into American society. Though far smaller than the American Legion, which claimed 850,000 members within its first year of its existence, DAV membership rolls topped 25,000 by 1922 and had 1,200 local chapters and state offices nationwide. Overlap between the DAV and the Legion was unmistakable; roughly 90 percent of DAV members were also legionnaires. In fact, Marx helped to found the Legion’s National Rehabilitation Committee.

Together, the two organizations placed veterans’ disability at the forefront of the push for veterans’ rights and benefits, including for “shell shock” or what today would be classified as PTSD. Due to the organizations’ efforts, in 1921 the U.S. government established the United States Veterans Bureau, a precursor to today’s U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

The Red Cross and the government also acted independently to address disability. In 1917, the Red Cross opened the first institution dedicated to training amputees and individuals with damaged limbs—The Institute for Crippled and Disabled Men in New York City. Though not initially established for veterans, the institute soon found itself inundated with World War I soldiers. In addition to rehabilitating injured soldiers, the institute produced and distributed 50 pamphlets, broadsides and books focusing on rehabilitation in the first year after the Armistice. During 1918, the institute distributed six million copies of “Your Duty to the War Cripple” to New Yorkers.

The government established the Federal Board for Vocational Education in 1917; it produced the first studies on veterans’ disability. The following year, the Smith-Sears Vocational Rehabilitation Act passed, providing for rehabilitation and vocational training for disabled veterans.

Despite these efforts, the treatment of disabled veterans varied widely, and attempts to streamline it largely failed. Veterans lodged numerous complaints related to poor dining, housing and rehabilitation facilities. Counselors, meant to help steer veterans toward rehabilitation and vocational training, were seen by many veterans as distant and uncommunicative. Black veterans endured racial discrimination, greatly diminished facilities, and systematic neglect.

Of the roughly 330,000 veterans eligible for rehabilitation, nearly half received some amount of training. It came with a steep price tag, however; in 1927 alone, the cost of rehabilitation exceeded $400 million. The following year, the vocational education board expended half a billion dollars in compensation for veterans.

Though not exactly a success story, the government’s role in rehabilitation did expand the development and institutionalization of the veterans’ welfare and demonstrated a commitment to restoring veterans to societal productivity.'

FYI Lt Col Charlie Brown MAJ Byron Oyler Maj Robert Thornton SSgt David M. MAJ Roland McDonald MAJ Bob Miyagishima Maj Bill Smith, Ph.D. SFC William Farrell PO3 Edward Riddle Kim Bolen RN CCM ACM 1LT (Anonymous) SPC Michael Duricko, Ph.D SPC Michael Terrell SFC Joe S. Davis Jr., MSM, DSL SMSgt Tom Burns SMSgt David A Asbury SGT Jim Arnold PVT Mark Whitcomb

(6)

(0)

Read This Next

Disabled Veterans

Disabled Veterans WWI

WWI Military History

Military History